Ecological Dynamics

Listen to this post

I was recently introduced the sports psychology methodology called Ecological Dynamics. It's an approach to skill acquisition for physical activities which is becoming widely adopted by contemporary coaching practices. Elite coaches across the globe are leveraging these strategies to achieve remarkable success in top-tier sports.

I believe Ecological Dynamics can apply broadly to skill acquisition in fields beyond sports. In fact, I'd argue that it's a direct reframing of Constructivism, a pedagogical movement which began way back in the 1920s (with every Education undergraduate's favourite reference: Jean Piaget).

Let's start by breaking it down.

Ecological: The study of living systems and the way they interact with their environment.

Dynamics: How patterns emerge and adapt over time.

Ecological Dynamics: The patterns that emerge when living systems interact with their environments.

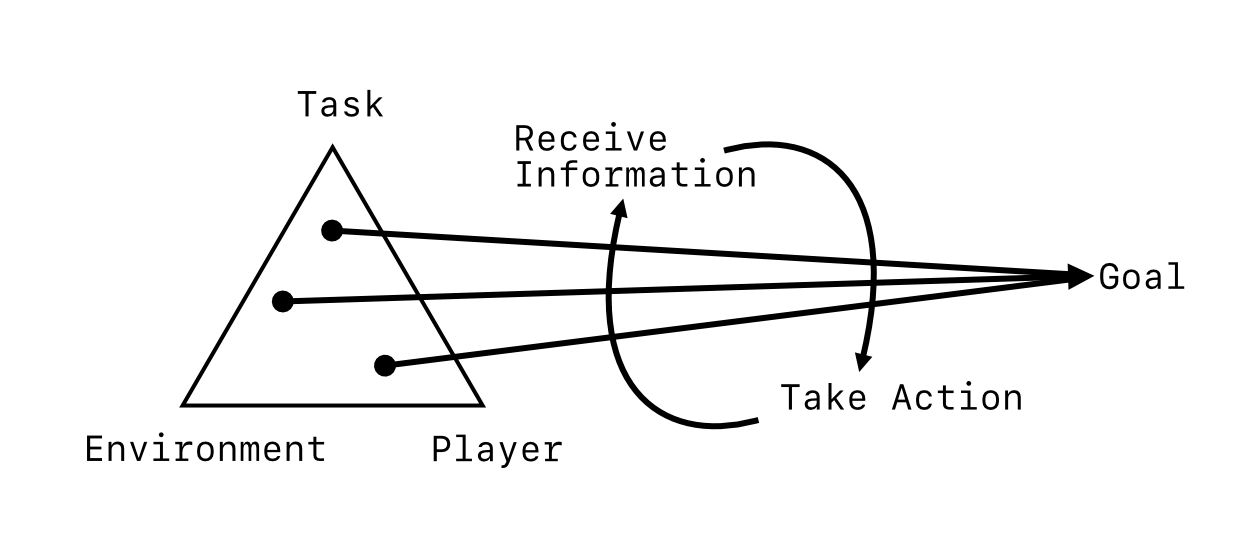

In sports, this creates a framework for analysing the movements and behaviours of athletes across a broad range of conditions. Rather than focusing on a very specific skill and repeating it in isolation, players are put into new environments (often by surprise) that challenge their movement, adaptability, and decision-making. Then, they study the influence of behavioural and movement patterns on the successful completion of a goal.

This approach is founded on four main principles, which define Ecological Dynamics.

- Functional variability: Intentional variations in the learning environment that encourage adaptability and exploration.

- Representative learning: Authentic and contextually relevant experiences.

- Attunement to affordances: Skill calibration through varied invitations to action

- Nonlinear progression: Skill acquisition that is collected from a variety of sources, not from linear progression or memorisation.

The Ecological Dynamics learning cycle.

We can apply these principles to skill acquisition outside of sports. As you'll see, each Ecological Dynamics principle aligns with a Constructivist idea.

I'm not trying to say that modern coaching is uninspired or plagiarising, but to remind us as educators that these ideas really do work, yet often go ignored.

Functional variability

Rote memorisation may be common practice in traditional learning environments, but its long-term effectiveness has been long disproven. Expertise is achieved not by "perfect practice makes perfect", but through functional variability, allowing adaptation to different conditions.

Students should be exposed to multiple problem-solving approaches, rather than a single rigid method. Play it fast, play it slow, play softy, loudly, staccato, legato, upside down and back to front.

Of course, this is already well established pedagogical practice. I came across constructivist styles of pedagogy through David H. Jonassen's mindtools. I'll quote him extensively here, as he's the easiest Constructivist writer to read!

Constructivism proposes that learning environments should support multiple perspectives or interpretations of reality, knowledge construction, context-rich, experience-based activities.

Representative learning

Yet another case where the best practices and routinely skipped over. We know that the more contextually relevant the learning environment, the better the learning outcomes! So, why do we line children up in classroom rows and hand them workbooks!?

In Ecological Dynamics, realistic environments are essential for effectively observing and developing skills. To practice a skill in a complex environment the simulation should be directly analogous to the game-time conditions. This allows cognition, perception, and action from the practice context to successfully transfer to the heat of competition.

In Constructivism, we see an emphasis on authentic tasks, which immerse learners in meaningful, real-world challenges rather than abstract drills, fostering deeper understanding and transferable skills.

Authentic tasks are those that have real-world relevance and utility, that integrate those tasks across the curriculum, that provide appropriate levels of complexity, and that allow students to select appropriate levels of difficulty or involvement.

Attunement to affordances

Affordances refer to the possibilities for action that an environment offers. In both Ecological Dynamics and Constructivism, learners develop skills by recognising and responding to these opportunities. Rather than following a prescriptive set of steps, they calibrate their responses through repeated interactions with a dynamic environment, refining their intuition and judgment over time (attunement).

In sports, this means athletes learn to perceive and exploit opportunities within a game – finding gaps in a defensive line, adjusting their positioning based on an opponent's movement, or intuitively reading a teammate's next move. The key is not rigid instruction but an adaptive, exploratory process that is refined with practice.

In Constructivist education, attunement to affordances means that students refine their understanding by actively engaging with their learning environment and adjusting their approach in response to real challenges. Instead of absorbing abstract knowledge in isolation, they develop intuition through hands-on exploration, experimentation, and feedback.

A young writer refines their craft not by rote grammar exercises but by reading their work, and iterating on it, recognising what makes their writing effective.

Monitoring involves checking on performance during execution to make sure that the processes are implemented correctly. Evaluation is an iterative process of constantly examining whether the pieces fit together, and if activities are going in the direction of reaching the goal...

Looking ahead means learning the structure of a sequence of operations, identifying areas where errors are likely, choosing a strategy that will reduce the possibility of error... Looking back means detecting errors previously made, keeping a history of what has been done and what should come next, and assessing the reasonableness of the immediate outcome.

Nonlinear pedagogy

Traditional education often assumes that learning follows a straight, predictable path. First, master foundational skills in isolation, then gradually build towards complex applications. This model treats knowledge as something to be stacked neatly, one block at a time. But real learning doesn’t work that way. Skills develop through cycles of trial and error, feedback, and adaptation, not through rigid, linear progression.

In Ecological Dynamics, athletes refine their abilities by engaging with ever-changing constraints rather than following a fixed training sequence. A basketball player doesn’t first perfect a jump shot in controlled conditions before facing a defender. They learn to shoot while adjusting for pressure, movement, and game dynamics. The complexity isn’t stripped away; it’s part of the learning process from the beginning.

The same applies to Constructivist education. A student learning a new language through conversation isn’t drilling vocabulary in isolation but responding dynamically to real linguistic interactions.

Determinism and predictability will not help us to become effective learners in the real world. Instructional design theories need to treat learning and instruction as open systems that receive input from many sources, such as individual differences, maturation, emotional states, and social-economic, cultural, and demographic factors, etc.

Ecological Dynamics and Constructivist education share a simple truth: learning happens best through real experiences, not rigid drills. In both sports and academics, skills develop through adaptability, exploration, and interaction with a dynamic environment. The best learning isn’t linear; it’s a process of finding meaning, seeking feedback, and adaptation.